DUTCH INDONESIAN MEMOIRS 1941 - 1948

MLD Marine Luchtvaart Dienst

or

DNAS Dutch Naval Air Service

KONINKLIJKE LUCHTMACHT Netherlands Royal Air Force

HANGER 6 Naval Airstation Morokrembangan

Page 3. 2ND MEMOIR ACCOUNT FROM HANGER 6

W. J (WIM) VERSNELL

D-Day and Europe

Wars end and return to England.

After a one-day postponement, due to bad weather, the invasion started on June 6 and with that a lot more sorties being flown by our and the other two squadrons. Sometimes four times a day and that meant a lot of in-between flight inspections to keep the planes airworthy. I was flat out with refuelling 6 aircraft and the regular petrol bowser driver did the other 6. The planes needed about 300 gallon each after every flight, that meant that the distance flown was not so great, as sometimes they needed 600 gallon each. Often a plane did not return and then a spare one was used for the next flight. Twelve planes made one squadron each of two flights of six. We usually had about twenty planes in the squadron. Losing one plane was not such a big problem, but losing the crew was something else. So, it was not so long before we had to fill up the crews with British and Commonwealth servicemen. There was even a pilot from Jamaica in our squadron.

On October 9 the main party of 6320 Servicing Echelon was sent by LST to Ostende in Belgium and we drove in convoy to Base 58 Melsbroek near Zaventhem, about 20km from Brussels. Me in the old Bedford petrol bowser. In Zaventhem, we were to our surprise billeted in a convent, where probably the German airforce was billeted before us, in rooms as big as hospital wards. There was plenty of room for us and the beds were already there, vacated by the Germans. So, we were lucky not to have to live in tents, although we were trained for that in Swanton Morley. You can be lucky sometimes.

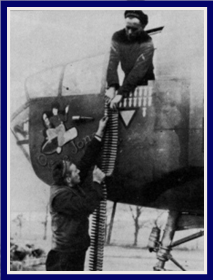

B25 Mitchell painted in D-Day stripes.

Melsbroek was a typical German airfield with hangars, constructed in a way that they looked like farmhouses. Two runways were in use and on the third runway all the Mitchells of the three squadrons were parked next to each other, squadron by squadron, about 60 planes in all. It was about ten minutes' drive from the convent to the airfield. I had the honour of driving the boys of 320Sq. to the airfield very early every morning after a quick breakfast in the convent. During our stay there, we had flying bombs coming over at night and they were meant for us. It lasted until all their launch sites had been knocked out, which took quite a while.

Zaventhern was a small village in those days, but there was a movie theatre and a few bars also there was an ice cream parlour which was always full of Yanks and us Dutch East Indies blokes. The owners were Papa Sous and Marna Stefanie, who did a roaring trade. There was a tram close by, which went to Brussel. We often went to Brussels and that was an eye opener. You could buy anything, just like there had not been a war going on. I don’t know how the Belgians did it, but you could get real good meals and plenty of drinks. I bought a second-hand camera there, as I had no camera in England, where taking pictures was forbidden for security reasons but the Germans knew everything about Melsbroek, so security was not so strict. I took pictures of all different aircraft, even of the German ones, which were left behind.

The photograph shop owner in Zaventhern must have made quite a few extra francs from those photos as he made a lot of copies and sold them in his shop neatly bundled in packets of ten. I happened to see them displayed in his shop window and I had no copyright, otherwise I might have made a few extra bob too. Most of those photos got stolen on my trip back to Indonesia, but more of that in a later chapter.

Meanwhile we were all working hard, keeping the kites flying. No extra medal was pinned on our chests for the good work. Soon the winter set in, and the 1944 winter was bitterly cold. That was the first time for most of us to see it snowing, as in the winter of 1942 and 1943 there was no snow at all in England. It was that cold at times that the petrol which was dripping out of the hose of the bowser was sometimes frozen in the early morning. Practically every morning we had waky-waky at four and I swore to myself that if I ever got a civilian job after the war it had to be a 9 to 5 job.

Our food was prepared in a field kitchen with as usual dehydrated potatoes, which tasted and smelled like pig food. As a matter of fact, we were always given those dehydrated potatoes even when we were still in England. They were packed in those four-gallon tins, which were in pre-war days used for kerosene. But outside the RAF stations in England, you could always buy fish and real chips. Also, in those days I had forgotten what an egg looked like, it was always scrambled eggs made from egg powder, also packed in those four-gallon tin cans. No wonder I was as skinny as a rake, even though I drank a lot of beer. Now I've got a sizeable pot (belly) and I don't drink as much beer any more just half a pint when we go out to lunch, which is every day, except on Sundays, when we eat at home. We are getting lazy in our older days, but why not?

There was a canal on the border of Achmer called Mitteland Kanal. On the other side of the canal were the barracks where the Luftwaffe-boys had been living before we took the show over. For the moment it was out of bounds for us, as there were a lot of booby-traps in there. They had to be cleared first by bomb-disposal units, and anyway the bridge over the canal had been blown own up. After the camp had been cleared of booby traps and some sort of bridge had been improvised, they put the NAAFI canteen there complete with Russian barmaids, at least I thought they were, as I could not understand their lingo. We still had to live in our tents and made stretchers from bits of wood lying around. It was quite comfy.

One day we heard an explosion on the other side of the canal and some of us went down to look what happened. A couple of chaps from the British squadrons had taken a bed out of the German barracks and carried it over the pathway on the bank of the canal to put it in their tent. However, they stumbled and fell into the ditch next to the pathway which had not been cleared yet by the bomb disposal units and fell on a booby trap or landmine and were blown up.

Further research has shown that the men were from 320 Squadron and Dutch, not as Wim says from a British Squadron.

Sgt. Wnr MLD. Johannes (Joop) Bootsma 50 Mission posthumously awarded the Flying Cross.

Born 7 Feb 1919, s'Gravenhage NL

Died 2 May 1945 Achmer Camp.

Sgt Vlgt Schutter MLD AdrianMachiel (Arie or Janus) Heijblom Missions 45 all with Bootsma

Born 14 Oct 1914, Ginniken-en-Bavel, Brabant

Died 2 May 1945, Achmer Camp

More information on Dutch Air Crew from both 320 & 860 Squadrons plus other casualties and their aircraft can be found at this excellent site "Lost Rob Philips Memorial Archive Index at,

http://aircrewremembered.com/1945-05-02-loss-of-sgt-bootsma-and-sgt-heijblom.html

The hangars on the airfield were camouflaged as usual like farm houses. In one of them the Germans had painted on the wall inside “Wir kommen wjeder” (We'll be back). In another hangar somebody saw a toolbox and when he opened it, it was full of tools. He closed it again to take it with him. When he closed the lid, the box exploded. It had been booby trapped with fatal results. So, the place was not too safe to roam around anywhere until the bomb disposal unit had checked everything.

The three squadrons making Wing 139, only made one operational flight from Base 11O (Achmer) as the war was over on May 5th. The NO-U went on this last operation but returned early as there was trouble with the compass, so missed out on the 137th. bomb painted on her nose. A few weeks later she was flown away to get decommissioned. I felt like losing one of my family members. The next day the KJ 7OO the new NO-U was standing on her spot.

On the 5th. of May 1945 when the Germans capitulated, I was as usual tinkering around with the new NO-U when I saw a big four-engined plane circling overhead. It was a Focke Condor from the Luftwaffe, wheels down, ready to make a landing.

As I was very curious to see what was going to happen, I ran down to the end of the runway, together with some RAF blokes who had the same idea. The plane landed and pulled up on the runway close to us. The pilot shut of the engines and the door in the rear opened. The crew hooked a step on and down came about half a dozen very high ranked Luftwaffe officers with coats on with those red revers, followed by lower ranking officers and the crew. The Condor was standing in the centre of the runway, so no other plane could land or take off. At that moment a jeep came tearing down with the RAF duty-officer in it, yelling tell those bastards to push that plane off the runway. Nobody obliged, as the RAF blokes did not speak German and the Germans pretended not to understand, mainly because he had called them Bastards.

The duty-officer saw me standing there with my Dutch Navy cap on and bellowed "You are Dutch and of course can speak German. Tell them to push that plane off the runway. So, in very bad German me a L.A.C. ordered the generals or whatever they were to push the plane off the runway. We all had to help them as the wheels were nearly as tall as me. It still was heavy pushing A truck came later to take the Germans away. They had been smart because they came from Eastern Germany and were escaping the Russians. They preferred to be taken by the Allies, instead of the Ruskies.

In our spare time we often went scouting around the airfield. We were not allowed to speak to the German population, that was called the non-fraternization policy, but we did so just the same and went into farmhouses to trade a bar at chocolate or a bar of soap for eggs, we started to look like eggs in the end. We had long conversations with them. At first, they were a bit hostile towards us, as they thought we were going to harm them seeing we were not like the Russians that soon changed. What scared them most was that we were walking around with our rifles, as we were part of the occupation army.

It must have been in the start of August 1945 that 320 squadron returned to England. For some reason I cannot remember much of this time. Our blokes from Hangar VI were stationed for a while at a RAF base. I cannot remember the name of the station. It could have been RAF Fersfield, but I do remember that it was there that we heard about the Atom bomb being dropped on Hiroshima, but at that time we did not know what an Atom bomb was, but a few days later after a second bomb was dropped over Nagasaki, there were rumours that Japan had capitulated.

Not long after our group was transferred to HMS Ambrose in Dundee, the submarine base where the Dutch submariners had been operating from. We were to wait there for transport back to Java.

It is at this point that I sadly lost contact with Wim. I had been diagnosed with a brain tumour and after neurosurgery and a long period of treatment and recuperation my priorities became more singular.

Another Visual Memoir of Ed Hoenson AC GUNNER 320 Squadron https://youtu.be/WARpDHRdCKA