DUTCH INDONESIAN MEMOIRS 1941 - 1948

MLD Marine Luchtvaart Dienst

or

DNAS Dutch Naval Air Service

KONINKLIJKE LUCHTMACHT Netherlands Royal Air Force

HANGER 6 Naval Airstation Morokrembangan

Page 3. Ceylon, South Africa and beyond.

The next morning our group was mustered on deck and one by one we passed a doctor who gave us a quick check up and shots then we went on to a table where a lieutenant and a yeoman sat who took all our statistics. For a fleeting moment I toyed with the idea to give my birthday as 1924 instead of 1925, that would have made me a year older. What gave me the idea I don't know but I soon dismissed it as silly, especially when it was my turn to face the lieutenant and the yeoman. The lieutenant turned out to be a paymaster and he paid us out in British pound sterling, how much I don't remember. That afternoon we were allowed to go ashore, and the first thing I did was hit a restaurant to eat my fill of rice with curry. I could not communicate with the people, as I didn't speak English or Hindu. I wandered around a little bit and looked at shops with lots of jewellery, but I was not interested and soon got bored and went back to the ship.

There were several guys who had themselves tattooed but I didn't go for that. Although several of my buddies said that Ceylon had the best tattoo artists in the world, it didn't cost much, and they tried to talk me in to having a one but I refused.

I lost track of the date. and didn't even care what day of the week it was, all I knew was that I was far from home, in a foreign country and only God knew how long it would take before I would see my parents again. Sure, I had my buddies, but they were in the same boat as I was.

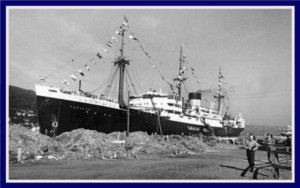

Our group was split up, and parts of our group went to England and were issued blue winter uniforms and winter gear. After a couple of days, we were all transferred to a troop transport ship. It was the converted luxury liner "New Amsterdam" from the Holland America Line, and we were on our way without convoy to Durban, South Africa.

The Nieuw Amsterdam

Extract from the East Indies Fleet Admiralty Diary

Naval History.net https://www.naval-history.net/xDKWD-EF1942.htm

The Nieuw Amsterdam left Colombo on the 19 March 1942 and sail unescorted to Durban South Africa arriving on the 28 March 1942. Onboard were 700 Dutch navy personnel and 600 European Passengers.

We arrived in Durban and were transported to "Clairwood" camp a British transit camp for armed forces. There were all kinds of nationalities in the camp Greek sailors, British India soldiers, Australian soldiers, and English sailors. They were coming out of the Asian war theatre and regrouping. For the first days we had to stay in camp. Our apprentice group was now down to twenty-five men but there were other groups added, signalmen, radio operators and sailors. Altogether there were seventy-seven enlisted men, three chief petty officers, all instructors and two officers our commanding officer and his exec. On April 20, 1942, we all posed for an official navy photo and went down in the annals of the Royal Netherlands Navy as the contingent of evacuees destined for the Netherlands West Indies.

Those who were issued winter uniforms were already gone and we just waited. After a few lectures of "apartheid" and the colour bar we were allowed to go on liberty to town, but it was not much fun as we were hit with apartheid as soon as we stepped out of the bus. In downtown Durban we just did what we usually did and if they didn't like it well, that was their problem. In some stores we were tolerated and maybe it was because we were so young and in uniform. I didn't go ashore much anyway just a couple of times with Ben Portier. Ben bought a ukulele and learned to play it and soon was pretty good at it. We mostly stayed in camp and in the evenings went to the canteen. After we were refused in church, I thought, well this is it. As far as I'm concerned, they could all go to hell.

We were once again moved. This time by train to Cape Town in the shadow of Table Mountain, and we were put in a South African army camp awaiting transport to the West Indies or America. Since our group consisted of Indonesians, half-cast Indonesians and only a few who were fair skinned enough to pass for white, we were housed in a segregated barrack with our own kitchen and mess hall, no big deal. Several fellows volunteered to cook and every day there were fresh rations brought and the guys cooked up some great Indonesian meals, we had rice three times a day and it was great, just like home!

Among the men in our group was a guy that I knew from Bandung when I was with my uncle. He was in the same apprentice teacher's class as my older cousin Louise Rugebregt, and he remembered me as one of his students in third grade. His name was Bob de Bie. He was quite a bit older, in his late twenties, and one day we both went ashore, and he helped me buy a camera, my first camera, an Argus C1, made in the USA. Bob was a radio operator and spoke fluent English, and we palled around quite a bit talking about old times in Bandung, but I never told him how mean my aunt Ceciel was. I could get along with my cousin really well and she was more or less a big sister to me.

One day, we were all marched to the armoury and were issued rifles and an ammunition bandoleer with ten clips each (fifty rounds). The rifles were a sorry mess. They were Italian rifles from the Ethiopian campaign when Mussolini in a brave moment decided to invade Ethiopia and had his butt kicked. The rifles must have been a war booty, at least that is what the South African sergeant said, who by the way was very reluctant to issue the rifles, as at that time the natives in the South African army were only outfitted with the short spears and shield of the Zulu warriors and only when they were standing guard in uniform! We were hit once more by apartheid. We spent a couple of days cleaning the rifles and getting them in safe, usable shape, and went through a couple of half- hearted drill exercises. There were a few South African families from Dutch origin who still spoke Dutch and invited us into their houses, but it was not so spontaneous as they would like it to appear, and after two visits I quit.

It is at this point that Frank and my father Robert (Robbie) parted company. He was bound for England, and we take up his life of a Dutch Indonesian serviceman on the Home Front.

You can continue Frank's story until they were reunited some years later.

From here on Franks continues to tell his story.

The day came that we were told once again to pack our gear and were on the move again. This time we were to board a ship and sail to the West Indies or maybe America. We hopped in two trucks but this time it was different as we were armed, and our gear went in a separate truck. Some place down in the harbour area we were unloaded and lined up and had to march to the ship. It was not so far, but it was through a coloured residential and industrial area and needless to say that we drew quite a crowd of onlookers, all of them people of colour. I could not help picking up some of the remarks, as South Afrikaans is similar to Dutch as a matter of fact it is old Dutch, the language of the Boers. The people could read our cap ribbons which read "Royal Navy" in Dutch, which was as I said similar to Afrikaans but what royal navy, certainly not the British, and why was it in Gothic. There was of course, the astonishment that we were carrying weapons, and their remarks were: "They are not English and they're carrying rifles, all long rifles like the "blankies" (whites)".

At the dock we found our gear stowed by the gangway, and we boarded another Dutch freighter. Her cargo holds were converted to living quarters for troop transport, with mess tables and bunks and hammock hooks, each found a place to sleep or hang his hammock, and we stowed our weapons.

The Tarakan

The name of the ship was the "Tarakan" a diesel-powered converted freighter. Next, we were notified that we were to guard and transport a group of prisoners to the West Indies and that they would be held in the forward cargo hold which was also transformed for troop transport. A watch and guard roster were made up, and we waited the arrival of our "guests". Pretty soon they arrived, about twenty-five of them, all white, and were led to the forward hold where they were to stay until we arrived in the West Indies. At first, we thought that they were PoWs, but we learned later that they were Nazi sympathizers and draft refusers. The beauty was that they were all South Afrikaners and white, and here we were all men of colour holding a gun at them and wouldn't hesitate to shoot if they were to try something funny. They were our prisoners and we made sure they understood.

The Atlantic crossing went off without a hitch and we were not sailing in convoy.

I had my seventeenth birthday at sea during the crossing.

We were now about eight months from home, without contact. Our first landfall was Paramaribo, Surinam a Dutch colony on the mainland of South America. We went ashore and soon found out that there was a whole Indonesian colony there, mostly Javanese farm labourers who had been migrated by the government to settle in Surinam. I soon found a restaurant that was run by a Javanese family, and I was pleased that I could have some familiar dishes, just like my mother use to make.

We stayed a couple of days and during that time our prisoners were taken off the ship and turned over to the military police. After a few days we set out to sea again not knowing where too. The next port was Port of Spain on the island of Trinidad a British colony then. Here we disembarked and were now transferred to a British Naval Base and were assigned to a barrack. A senior hand was assigned to look after the barrack and its population, and we were left to enjoy the beach and the beauty of the island. Little did I know that I was to be back on this island later as a crewmember of a destroyer escort.

From Trinidad we were flown to Curacao one of the islands of the Netherlands Antilles -West Indies, to the town of Willemstad. This island held the biggest oil refinery complex in the world. Several big oil companies like Shell, British Petroleum, and several American oil companies had their refineries there. The whole island area was practically one oil refinery with a natural deep harbour and close proximity to north and South America. Oil tankers with crude docked and left with gasoline and refined products in a steady stream day and night.

During the immediate period after America entered the war, they refused to lower the publics moral and decreed that the Florida coastline would not be subjected to any blackout restrictions. As a result for nearly six months merchantmen sailed from the Caribbean unescorted along the coastline brightly silhouetted into the sites of the 21 U boats sent there by Admiral Donitz.

By June 1942 no less than 505 ships had been sunk, many within site of the Florida beaches.

We were housed in the ancient navy barracks of Watenford. It was an old fort dating back to the late seventeen hundreds. We finally were back on a normal Dutch navy base with the normal routine. The sailors, signalmen and radio operators were assigned to several units and the apprentices were put in a row and divided over mainly three branches, electricians, torpedo men and ordnance technicians. I happened to be assigned ordnance technician. Schooling started and days went by with regular classes in electronics, mathematics and in my case, artillery, and ordnance. There were also practical sessions and I worked on the maintenance of the shore batteries and in the navy arsenal.

I realized now that I'd better stop hoping for a quick return home, as I now realized that home was no more. It was occupied territory and the Japanese were not about to give up their captured territories.

Soon I got word that I had my first ship assignment. I was to report to HNLMS Van Kinsbergen a destroyer escort, sailing convoys in the Caribbean Sea between Trinidad, Miami, and New York. I got my dress blues and some extra winter gear and packed my sea bag and hammock and got ready to go on board. I was told that the ship would be in early next morning and a tug would take me to the ship. What, to my surprise, happened was that the next morning a convoy appeared over the horizon and several tankers made their way into port while the destroyer kept patrol on the perimeter for German U-boats which were abundant in the Caribbean waiting for their prey of tankers.

The sea was pretty rough and the tug I was on headed straight for the destroyer. When we were alongside a rope ladder went over the side and somebody shouted, "Get that lazy skeleton on board fast". I grabbed my hammock and started up the ladder which was not so easy in rough weather and a moving ship. I made it on board, and somebody threw a rope overboard and hoisted my sea bag up on deck. I saluted smartly and reported as told to the officer of the deck. I was seventeen years old, two years in the navy and assigned to active sea duty and I was excited.

HNLMS Van Kinsbergen 1942

The officer of the deck was a big man and kind of looked me over as to try to make up his mind what to do with me. Finally, he summoned the gunnery officer and turned me over to him. In the meantime, the ship picked up speed again and resumed its patrol pattern until all the tankers were in port and we resumed our course with the rest of the convoy of merchant vessels to Trinidad. I was to report to the chief of the boat and spend the rest of the day getting my bunk, watch assignment, where to go in case of general quarters, etc, etc. I was introduced to the ordnance crew and had a talk with the chief ordnance technician an older warrant officer and the division officer who was also the gunnery officer. It took the rest of the day and at five in the afternoon I was through and got ready for dinner and waited until eight o'clock. It was my first watch at sea in combat.

Life went on at sea and my daily work was helping with the maintenance of the fire control and in the afternoon while on duty in the fire control room a chief petty officer gave me instructions on electronics and fire control systems on Mondays and Wednesdays and on Tuesdays and Thursdays it was math and artillery and on Fridays Navy regulations and procedures. All my instructors were members of the fire control crew, and the books were the regular Navy Technical schooling books. Because I was still an apprentice, my regular sea watch was constant from eight to midnight the first watch, with whom ever had that particular watch. The rest of the crew rotated watch every trip.

We sailed convoys between Trinidad, Guantanamo (Cuba), Miami, and New York. It was mostly tanker convoys, and we lost several tankers to German U-boats. When hit, the tankers usually went up in flames and two PC cutters that were part of the convoy protection group did rescuing of survivors. Only once did we pick up survivors, that was when the USS "Erie" was hit and was beached at Curacao after most of the crew went overboard. We lost several ships out of our convoys as the Caribbean waters were a haven for German subs.

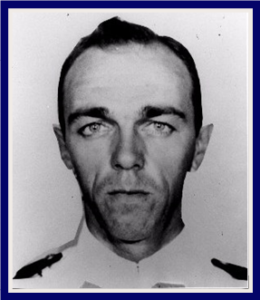

USS ERIE (PG-50) Gunboat, 213 crew and Floatplane aft. LT.(j.g) Frank Greenwood 1915-1942

Lt. jg Frank Greenwood. Died on board the USS Erie 12 November 1942 aged 27. His mother Mrs. Laura Greenwood sponsored the USS Greenwood launched on the 21 August 1943 and commissioned on the 23 September 1943. The Erie was hit by U-163 under the command of Korvkpt. Kurt-Eduard Engelmann. After being hit she caught fire and was steered to the beach and abandoned where she burned for days. The rest of the crew were picked up by land forces from Willemstad. Further info and history at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/USS_Erie_(PG-50)

Spring 1943, we went into dry-dock in Norfolk, Virginia for a paint job and expansion of the bridge deck to hold four 20 mm batteries two on each side. We also got a new radar and fire control system and submarine detection system, (ASDIC). While the ship was in dry-dock and US Navy and civilian technicians and dock workers were swarming over the ship, we were taken off ship and sent to New York for a weeks, R&R while half the crew stayed behind on watch duty and were to be relieved when the first half came back.

It was during that time that I started to enjoy beer, as the Dutch navy ships are not "dry" and we could get as much beer as we wanted nobody questioned my age. I was the youngest crew member, still underage, and the rest of the crew was much older. Almost everybody was married and had their families in occupied Holland. There was at least a ten-year age difference between me and the other crewmen. I could buy as much beer as I wanted, and I did. We bought the beer by the case and put it in a combined cooler with our name on the case and nobody would ever take a can out of somebody else's case, same with the soft drinks which we didn't have or cared for much, grapefruit or pineapple juice was all we had.

When we returned to ship, I noticed that the colours were changed to the darker colour that meant North Atlantic routes. Another thing I noticed was that where there was once an empty space on deck there was now a battery of 40 mm anti aircraft-guns, very impressive I have never seen one like it. I looked at it in admiration when the gunnery officer walked up and told me that we finally had our own battery back. I asked him what he meant, and he told me that almost three years ago, the battery, fire control and all, was taken off, to be copied by the US for the allied forces as at that time it was a superior piece of equipment. It was a Swedish made Bofors gun, 40 mm double barrel, and practically brand new. We were the only ship in the allied forces at the beginning of the war that was equipped with it. Our battery had served as a master from which copies were made in the U.S. and pretty soon they appeared on all ships, old and new, of the allied forces.

We returned to Key West, Florida, a destroyer, and submarine base to pick up a convoy escort it to Newfoundland and then returned to New York, which was now to become our station for convoys in the North Atlantic. The weather changed and coming into New York harbour and passing the Statue of Liberty, for the first time in my life I saw snow it was an impressive sight. We were docked at Staten Island pier #7. I'll never forget that because we were the first one to moor and the two other US destroyer escorts moored alongside us. This was because our electrical system was just the opposite of American and British ships. We had 220V AC and 11OV DC and needed a diesel generator on shore to supply AC power while the American destroyers could tap into the shore boxes with cables that had to be strung across our deck. At first it was not appreciated but after they found out that they could get beer on board our ship for a nickel, or nothing if they palled up with one of us, it was soon forgiven and from then on they showed their movies on our deck with beer!!

Weeks went into months, and we sailed convoys from New York to Miami, Guantanamo Bay, Trinidad and back to New York and north to Newfoundland and halfway to Iceland where the convoy was taken over by British convoy escort groups and back to New York, to load up provisions and fuel and oil. We were mostly not much longer than three days in port, so those days, had to be divided between work and liberty. We mostly stayed out on the town until the next morning depending on whether it was a hot or a dead town!! Several times we put into Curacao.

We stayed at the Times Square Hotel on 47th Street a stone's throw from Times Square and we lived it up! I had some money saved, as at sea you didn't need much and when we went into port, we just drew from our wages whatever we needed for a day in port. I couldn't believe my eyes and was overwhelmed with all the bigness of downtown New York. It was one big party, as service men and especially as allied forces we hardly ever had to pay for our drinks and usually restaurants gave discounts to service men. Theatres and movie houses were also discounted or reserved seats free. One night a friend of mine got two tickets for special seats in Carnegie Hall and we saw the performance of Jan Cupura and Martha Eghert in the Merry Widow. It was beautiful and we had a front row seat on the first balcony right in the centre section.

December 1944, we left New York and picked up a convoy. I noticed that our two US pals were not coming along and wondered where we were heading. Neither were we flying the convoy leader's signal flag the diagonally red and yellow striped flag (signal flag "Y"). The convoy was also different, no tankers this time, only freighters and two liners and the convoy leader was a British cruiser. I never found out what her name was. And after a couple of hours, word spread that we were heading for England. Coming closer to England we had more air cover from the British RAF Coastal Command and the merchant ships started to let up their anti-aircraft balloons. We reached Plymouth without an incident, and as the convoy turned into port we separated and sailed for London.

We docked in Shadwell docks London, and I saw for the first time the devastation the German Luftwaffe had inflicted on this city.